By Richard Pagliaro | Sunday, September 8, 2019

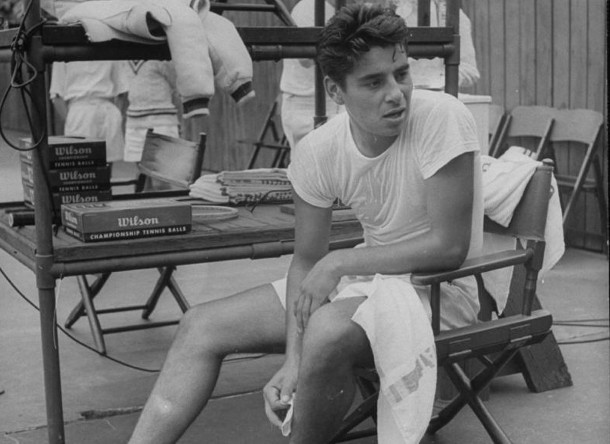

Seventy-years ago this month, Pancho Gonzales pulled off the greatest comeback in US National Championships history in a record that remains unmatched.

Photo credit: International Tennis Hall of Fame

NEW YORK—Signs surround us everywhere.

Sometimes, we’re too busy scanning screens big and small to realize their message.

TN Q & A: Cliff Drysdale

TN Q & A: Gonzales on Gonzales

The US Open celebrates the power of the public park pioneers.

The USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center home to Arthur Ashe Stadium with the newly-unveiled Althea Gibson statue out front honor three American champions who each honed their skills on public park courts.

This month marks the anniversary of the greatest stand ever made by a public park player—and game-changing champion—in tournament history.

Seventy years ago, Pancho Gonzales, a self-taught player from Los Angeles’ Exposition Park, roared back for the most rousing comeback in U.S. National Championships—now US Open—history.

Widely regarded as one of tennis’ fiercest fighters, a gallant Gonzales made history becoming the first man to fight back from a two-set deficit to win the U.S. National Championships final with a gripping five-set victory over 1942 champion Ted Schroeder to successfully defend his title in an epic '49 Forest Hills finale.

To this day, Gonzales remains the only man in U.S. National Championships/US Open history to ever fight back from two sets down in the final and take the title.

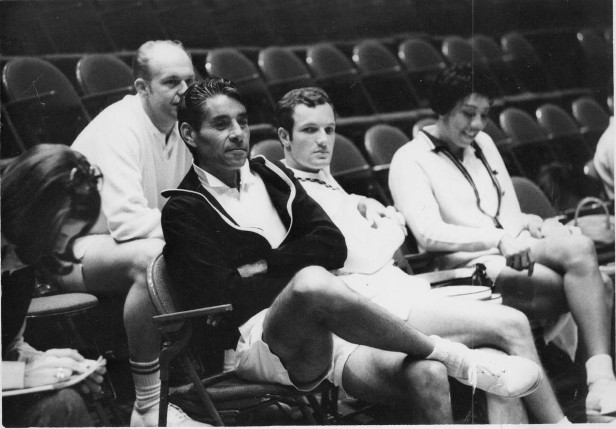

Photo credit: Life Magazine/International Tennis Hall of Fame

In 1948, a 20-year-old Gonzales arrived in Forest Hills ranked 17th in the United States and slashed through the field with his dynamic serve-and-volley style sweeping South African Eric Sturgess in a commanding straight-sets final.

The kid from Los Angeles' south side was hailed as “the natural” with a thunderous serve igniting an electric all-court game. Initial praise turned to skepticism and outright ridicule after Gonzales fell to Geoff Brown in the 1949 Wimbledon round of 16.

"There was speculation that Gonzales’ 1948 U.S. victory had been a fluke," Hall of Famer Bud Collins wrote in his Tennis Encyclopedia. "One writer flatly called him a 'cheese champ'—which is how Gonzales got his nickname of 'Gorgo' short for 'Gorgonzola'. "

Defending his title in '49, Gonzales turned the tournament into a statement of identity.

The top-seeded Schroeder worked through a tense opener, 18-16, then took the second set, 6-2, to put the champion on the brink.

Undaunted, Gonzales' physicality, defiance, aggression and all-court virtuosity wore down Schroeder.

Unleashing a relentless serve-and-volley attack, Gonzales faced the pressure racing forward. Gonzales roared through the final three set, 6-1, 6-2, 6-4 successfully defending his title in a moment he regarded as one of his career peaks.

“I don’t know if there’s any title he appreciated more than his second straight US National Championships,” Gonzales’ son, Richard Gonzales, Jr., told Tennis Now in an interview before the US Open. “Obviously, it was a great comeback match. More than that, he showed himself—and everyone else—the great determination he had.

"I think that he would have told you that match was one of the most important of his career because that great determination he showed in that comeback stayed with him throughout his career. Whether he won or lost he put that effort and fight and determination into every match he played. He had an amazing ability to focus all of his energy and intensity on the point he was playing and that stayed with him.”

So did the park where he learned the sport watching the top local players—and picking their brains.

The oldest of seven children in a Mexican-American family, Gonzales was the son of a house painter and grew into a temperamental and riveting tennis artist.

"Most people don't understand the reason behind him exploding and things," Gonzales' brother told filmmaker Gino Tanasescu more than 20 years after his epic comeback. "To him, tennis is like being an artist. Playing the game and winning is not enough. It has to be perfect."

In tennis and in life, Gonzales was a dedicated serve-and-volleyer: Always moving forward to face the next challenge.

As a child, Gonzales begged his mother, Carmen, for a bicycle.

One Christmas morning, the story goes, his mother presented him with a 51-cent wood racquet that turned out to be one of the greatest investments in tennis history. It was a purchase that would change Gonzales’ life—and set him on a four-decade tennis journey.

Immersing himself in tennis, the young Gonzales quickly developed a reputation as a renegade. As a teenager Gonzales was suspended for a year by the Southern California Tennis Association after informing them he was planning to quit school to focus on tennis. There was a burglary arrest at 15 and time spent in detention before a 17-year-old Gonzales joined the Navy where he developed his life-long cigarette smoking habit.

Gonzales would go nearly two-and-half years without playing high-level competitive tennis until his discharge from the Navy in 1947.

Photo credit: Life Magazine/International Tennis Hall of Fame

The next year, he stunned the tennis world winning Forest Hills setting the stage for his '49 defense and historic fight-back.

While it's possible his 70-year-old record may be matched someday consider Gonzales out-dueled Schroeder in record 67 games in that epic 1949 final. That record for most games ever played in a U.S. National Championships/US Open final cannot be broken because the Flushing Meadows major plays a tie break in every set.

As most devoted tennis fans know, Gonzales holds another record that will likely never be broken: He is the only champion ever inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame while still an active player.

These days, Gonzales is often portrayed as tennis’ archetype anti-hero: a raging, edgy, combustible, chain-smoking, race-car driving loner who viewed all rivals—and many fans and media—as threats he was committed to conquering.

The truth is, Gonzales had a great passion for talking tennis tactics and strategy with fellow players, was often very generous with his time and wisdom and was highly-respected as a mentor and teacher by champions ranging from Arthur Ashe to Jimmy Connors to Charlie Pasarell to John Newcombe.

"The inner resolve of Pancho Gonzales defied analysis. Gonzales had delighted in sharing his deep knowledge of the game with the younger American players of the 1960s before the advent of the Open Era,” Hall of Famer Steve Flink wrote in his book The Greatest Tennis Matches of the Twentieth Century. “To most of these young men—Arthur Ashe and Cliff Richey were others in that camp—Gonzales was a hero.

"They had grown up watching and reading about him. They recognized in Gonzales much of what they aspired to be themselves. He embodied the ineffable characteristics of a champion. Pancho's advice on strategy and tactics was always welcome."

Connors, who partnered Gonzales in a dream doubles team of premier returner with iconic server, famously described watching his ferocious, fiery intensity as “like staring into the flame of a fire—you couldn't take your eyes off him.”

"There was only one boss on court and that was him," Connors said of his mentor and partner.

Why does Gonzales’ great comeback 70 years ago still resonate today?

Serena Williams, who grew up learning the game on the public park courts of Compton, California, a few miles from where Gonzales played at Exposition Park, continues her quest to match Margaret Court’s all-time mark of 24 Grand Slam singles titles.

While a 37-year-old Williams went down to 19-year-old Bianca Andreescu, suffering her fourth straight major finals lost in Flushing Meadows on Saturday, she can look to fellow L.A. native Gonzales, who remained one of the best players on the planet into his early 40s, for longevity inspiration.

Despite being a heavy smoker, Gonzales was a spirited tennis lifer who never lost his burning desire and passion for the sport he picked up on a public park court and helped propel into a pro circuit. Years later, Gonzales returned to Exposition Park and bought the tennis shop there reinvesting in the sport he reshaped.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of Rod Laver winning Forest Hills to complete his second career Grand Slam in 1969.

Just four months after Laver’s Forest Hills triumph, a 41-year-old Gonzales summoned the gladiator within defeating Laver in a classic five-set conquest at New York’s Madison Square Garden. That packed MSG match drew more fans than Laver’s 7-9, 6-1, 6-2, 6-2 rain-delayed victory over Tony Roche in the 1969 US Open final at Forest Hills.

The charisma and competitiveness Gonzales delivered on court helped popularize pro tennis—and taught Gonzales a lesson about embracing reconciliation.

The man who broke barriers as a Mexican-American public park player dominating a largely white, mostly elitist, country club sport in America also shattered the walls between athlete and audience engaging fans like no other pro before him.

“When I was playing on the pro tours and I was the recognized champion, I was the villain," Gonzales told film maker Gino Tanasescu. "Because they were always for the other guy, the underdog. And I used to get out on the court and I used to build myself up to fight the whole crowd.

“I'd cuss them all out. They'd cheer for the other guy and I'd be feeling I'd be fighting the whole crowd and invariably end up trying to take it out on my opponent. And now I've changed positions being the old guy. They've picked me up and it helps. It really helps."

Photo credit: International Tennis Hall of Fame

The crowd tried to pick Serena up on Saturday night.

More than two years removed from her last title at the 2017 Australian Open, if Williams can continue to fight with the ferocity she’s shown and continue to put herself in position, she can still match Margaret Court’s record.

"The only thing you'll have left, when everything else is gone, is pride," Gonzales said.

The lesson Gonzales sends—70 years after his masterpiece comeback—is the staying power of the public parks player remains strong.

Sometimes, it's the outsiders who are the real game changers.

Tennis lifer Gonzales, who poured himself into every match as if his life was invested in its outcome, shows us immortal champions can defy conventional competitive expiration dates.

Next time you visit the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center stop by the court of champions.

There you'll find Gonzales, coiled and ready to strike his classic serve, right next to rival Tony Trabert and relative Andre Agassi.

A timeless champion who gave us the art of the classic comeback that remains unmatched seven decades later.