On Friday, April 29, the Junior Tennis Foundation will host the 24th annual Eastern Tennis Hall of Fame awards dinner at The Water Club in New York City. This year's inductees are Brian Hainline, M.D., chief medical officer of the United States Tennis Association; Robert L. Litwin, a senior national and world champion; Melissa Brown, the 1984 French Open singles quarterfinalist and winner of the Wimbledon Ladies' Plate; and Al Picker, the veteran tennis columnist of The Newark Star Ledger. Nancy Gill McShea has written profiles of each inductee here:

Melissa Brown

By Nancy Gill McShea

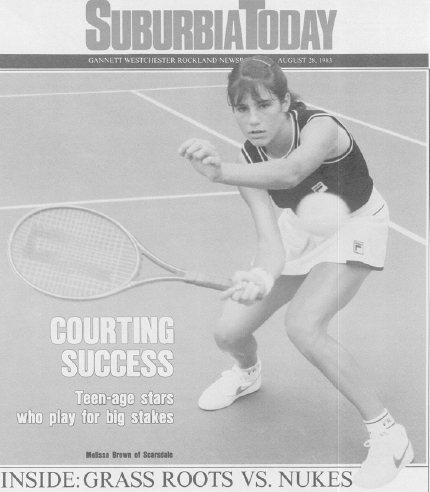

News travels fast in New York tennis circles when a young star emerges from the pack and defeats another young talent soon to be acknowledged as one of the greatest women tennis players of all time. We’re talking about Melissa Brown of Scarsdale, who in the early 1980s beat Steffi Graf three times in their early teens.

Melissa was a natural athlete, an honor student who starred on her soccer and basketball teams. But she was surrounded by tennis players -- her dad, Neil, was the captain of his tennis team at New York University; her mom, Nina, was ranked in Eastern Open singles; and her younger brother, Derek, followed suit and ranked first in Eastern juniors and tenth in the country – so tennis ruled in the Brown household.

By 1982 Melissa was ranked No. 1 in the USTA girls’ 14 division and newspaper reporters sensed that she was ready for primetime. Charles Friedman reported in The New York Times: “Melissa…tall with long, slender legs was the best junior tennis player in the country in her age group…1982 was a banner year…with a record 90 match victories against 15 losses and a collection of titles ranging from the summer national clay courts to the international Sport Goofy Disney Cup…which she won in Monte Carlo.“

Melissa defeated Steffi Graf at the Monte Carlo event, a mini Olympics that showcased eight of the world’s best young players from North America, Europe and South America. In that first meeting, Melissa was 14, Steffi was 13.

The most dazzling Brown-Graf encounter was a featured attraction at the 1983 US Open. Local fans lined up 10-deep on the sideline of Court 7 at the USTA National Tennis Center to watch the pair duke it out in the women’s qualifier.

This contest would count. They were two teenagers heading toward pro careers. Melissa was 15, Steffi was 14.

Renee Richards coached Melissa that day and gave an account of the match:

“Steffi was seeded second, with entourage of father, mother and assorted other assistants and a reputation already as a top prospect. I went over after practice that day and watched her hitting on a nearby court. Steffi was quick and athletic but…she took her forehand very late, almost off her back foot, and with a big backswing. Melissa had much more classic strokes, was very solid on both sides and more importantly, she hit the ball hard. I told Melissa, 'Listen, you know that Steffi makes big shots with her forehand but it won’t stand up to your ground strokes. Play her forehand, she will be late with it.'

“Melissa was smart besides being strong, and she did exactly that, dispatching Steffi, 6-1, 6-2. After Steffi cried courtside in disbelief – to this day that loss is considered one of the worst 10 defeats in Steffi’s pro career – she went home to Germany…and came back with the greatest forehand in women’s tennis. If Melissa’s career had not been interrupted when she went to college, we may have seen more battles between those two young stars.”

By the spring of 1984, Melissa was surging and expectations escalated. At the French Open, she had just turned 16 and gained worldwide attention, surprising the No. 6 seed Zina Garrison, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3, to become the youngest singles quarterfinalist in the history of that Grand Slam event.

One month later at Wimbledon, Melissa won the Ladies Plate consolation prize. She outlasted six players who had surrendered in the main draw, including Lea Antonopolis, 6-3, 5-7, 6-2, in the semifinals and Robin White, 6-2, 7-5, in the final. She again gained “a first” distinction, this time as the youngest player ever to prevail in the Ladies Plate event.

“My favorite match was when I beat Zina at the French getting to the quarterfinals,” Melissa said recently. “I was just starting out and she was No. 4 in the world…Just the emotion of reaching a goal, trying to do your job...and winning the Wimbledon plate was unbelievable.

“Getting a trophy from Wimbledon; nobody takes that lightly.” Her name is engraved on the trophy in the Wimbledon museum.

Later that summer, Melissa prevailed over Steffi Graf again in an exhibition at the Rye Town Hilton. They had become friendly and Melissa invited Steffi to her home for lunch. They prepared for the match by practicing together on the courts of the Scarsdale Junior High School.

Melissa’s first coach, Kit Byron, said she outslugged Steffi in that match, basically hit her off the court. “Melissa was a very strong girl,” Kit said. “She hit through the ball, very flat, and could drive the ball off both sides. And she was a quick learner, one of the most coachable pupils I've worked with. She dominated everyone in her age group. She was also one of the loveliest young women I have ever met in my life and one of the hardest workers I ever had on the court.”

Yet on August 16, 1984, Jane Gross commented in The New York Times that hazards awaited young kids who played pro tennis: “Miss Brown, currently ranked No. 43 in the world and a quarterfinalist at the French Open, is neither the first nor the youngest tennis prodigy to switch from amateur to professional play at a time when most of her friends are worried about junior proms, learner's permits or the availability of Michael Jackson tickets. In recent years -- outgrowing the age-group competition, uninspired by the prospect of collegiate play -- a parade of teen-agers has joined the women's circuit, among them Tracy Austin, Andrea Jaeger, Kathleen Horvath and Carling Bassett. The phenomenon has had mixed results and has stirred debate about whether teenagers are particularly susceptible to disabling injuries, like Miss Austin's, and to symptoms of emotional burnout, like Miss Jaeger's.”

Melissa said she was aware of the hazards of being one of those young pros in the early 1980s. She said it was like a free-for-all before the WTA adopted an age rule (January 1, 1995) which helped longevity.

She trained at Nick Bollettieri’s tennis camp while she toured on the pro circuit. Nick was impressed with her upbeat personality and her ability. “Melissa was a real fighter, she would do anything to win,” he said. “She was part of a talented group -- Arias and Andre (Agassi). They all worked hard.”

“I’m dedicated when I do something,” Melissa said, “but I wanted some balance, to be well rounded. Tennis becomes like a business, it requires a lot of preparation. I started to think about life after tennis so I went to college, which kept me grounded. It held me back with the tennis but I thought it was better for the long run.”

She enrolled at USC and then transferred to Trinity in Texas, from which she graduated in 1991. She continued to compete on the pro tour part time and won the USTA Circuit in San Antonio in 1987 without losing a set. In 1988 she defeated Pam Casale and Michelle Jaggard in advancing to the third round of the Australian Open before losing to Claudia Kohde-Kilsch.

Kathleen Horvath, who also turned pro at 15 and quit the tour to attend college and graduate school, said she thinks of Melissa “as friendly, smiling, bubbly. Melissa and I…sometimes trained together…Unlike most pro tennis player peers, Melissa was open, honest and sharing. She would happily divulge everything she did without me even soliciting information…I knew exactly what fitness drills, exercises she did…and how her practice match went…She would honestly ask for feedback without hesitation or concern that she was giving away anything. It was…endearing and I was touched that she trusted me and valued my opinion. I think this was a testament to her drive and desire to be able to put ego aside…to become a great player.”

Butch Seewagen played mixed doubles with Melissa at a tournament in San Diego and said, “I was already in my thirties and Melissa was just a kid; she was a great player and we had fun.”

Nicole Arendt remembers playing the same tournaments as Melissa and said, “Wow, what a talent!!!”

Another contemporary, Patti O’Reilly, said that Melissa was a “beautiful competitor on and off the court.”

Melissa’s friend Nick Greenfield called her a role model. “She was a tall, lean, quick and graceful player…an Amazon beauty…who punished the ball,” he said. “She hit clean winners from anywhere on the court and achieved tremendous success and fame facing older, top ranked players who were ruthless competitors. Had she not been so nice, there’s no doubt she would have been a top-10 player…but then she wouldn’t have been Melissa.”

Melissa finished college and retired from the tour in the early 1990s. “It was a difficult transition to focus on getting a normal job,” she admitted. “Nothing can be as rewarding as playing professionally where you grew up or getting to the quarters of a Grand Slam tournament. You think about the millions who are playing tennis and trying to strive...I cherish the past a lot more now than I did during the moment itself. I’m like wow, that’s not so easy to do. When you’re in the thick of things you’re just trying to reach the top and don’t realize the accomplishment until you’re older.”

But it was time for a change. Over the next ten years she first worked at Tennis Week with Gene Scott – “He helped me get started,” she said – and she ran successful pro-am charity fundraisers at Tennisport for Skip Hartman’s New York Junior Tennis League. She worked at Planet Hollywood in their event department and enjoyed a successful advertising career with Conde Nast’s Self magazine and Hearst’s House Beautiful.

Melissa and her husband Herb Subin are now busy raising two children: Brianna, 7, and Benjamin, 4. What’s next? “I’m going to use tennis to do something big again -- a charity fundraiser For Juvenile Diabetes,” Melissa Brown said. “I’m going to really start focusing on that now!”